48 years with Zilog Z80

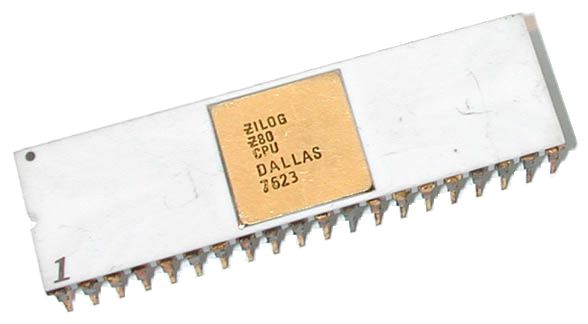

One of the early copies of the Zilog Z80 with a release date of June 1976. Gennady Shvets

The creation of the Z80 was the effort of several talented engineers who wanted to start their own company from scratch. Half a century ago, microprocessors were a novelty that could be created by small teams by modern standards. It was thanks to these early processors that the home computer boom occurred in the early eighties.

Recently Zilog announcedthat last orders for the original Z80 are accepted until June 14 of this year. The legendary Z80 remained in production for almost 48 years.

It is common knowledge that Intel made 4004, the first commercially available single-chip processor. In this achievement, some companies are undeservedly forgotten, and others are simply being erased from history.

In 1968, a young engineer at the Japanese computer company Business Computer Corporation, Masatoshi Shima settled down working on the 141-PF advanced calculator project. Sima's boss had experience at Control Data Corporation, an American manufacturer of mainframes and supercomputers, and suggested using a programmable approach in which different configurations of calculator models were achieved by changing the program. In response, Shima sketched out a design for the 141-PF, which has arithmetic units, multiplication units, registers, read-only memory, and even its own set of macro instructions.

At that time, Busicom was a mature manufacturer, founded as Nippon Calculating Machine Corporation and renamed Business Computer Corporation in the sixties. Nevertheless, Busicom was doing poorly financially.

Nippon Calculator HL-21. This adding machine is also meets with the new Busicom logo. Daderot

A chance contact helped the situation. The president of Busicom had a good friend, Tadashi Sasaki, at the much larger Sharp – they both graduated from the same university department. Sasaki informally offered to finance Busicom if the latter would develop integrated circuits for the 141-PF sketch as a computer system. Another condition of Tadashi concerned the choice of a partner for the project.

Japanese law allows for a small amount of assistance between companies, but this has gone further than this. Why did the Sharpovite do something like this? The fact is that Tadashi, in turn, had a professional contact at the American Fairchild Semiconductor named Bob Noyce. In 1968, Noyce and several other Fairchild employees quit and founded the startup Intel. At the same time, Sharp already had a contract with Rockwell, which is why it could not cooperate with Intel. Sasaki probably wanted to give his friend a small contract.

Busicom initiates negotiations with Intel, a cooperation agreement was reached in April 1969. In June, three Busicom employees were sent from Japan to the United States. One of the three is Masatoshi Shima. On Intel's part, Ted Hoff, a Stanford researcher who had previously studied electronic neural networks, was assigned to the project. In September, Stanley Mazor transferred from Fairchild to join the work on the calculator.

It was at this stage that seven microcircuits from Sima’s idea merge into one microprocessor. By the way, it owes its name to the fact that all devices for 141-PF in Intel’s internal naming were under the four-thousandth series, and in total four device models were installed in the calculator: four 4001 memory chips, two 4002 RAM chips, three 4003 shift registers and one 4004.

In October 1969, Busicom management came to the United States and assessed the work. At the end of the year, Shima returns to Japan to work on the calculator's firmware and documentation. The Japanese would arrive in America only in April 1970 and would be disappointed to discover that work on 4004 had not progressed at all, and Hoffa had been transferred to another project.

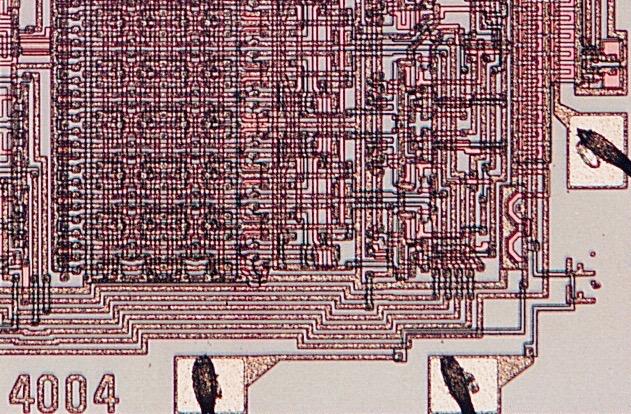

Fragment 4004. Intel4004.com

In the lower right corner of the 4004 crystal, two letters FF are distinguishable. These are the initials of the Italian-American physicist and engineer Federico Faggin, who joined Intel in April 1970. Before this Fagin was employed at Fairchild Semiconductor, where he invented self-aligned gate silicon MOS technology and developed the first commercial integrated circuit, the Fairchild 3708. In 1968, Federico remained in the US at Fairchild rather than returning to Italy: he was struck by the startup culture, which he had never experienced before. didn't experience this.

Federico moved to Intel just a few days before Masatoshi arrived, but they quickly worked together. To compensate for the delay, the Italian worked 80 hours a week. As a result of months of work by Fagin, Sima and Mazor, the first chips were sent to Busicom in early 1971. 141-PF is ready in March.

Fagin quickly realized that the 4004 was more than just the inside of a desktop calculator. With great dissatisfaction, he found out that the set of 4,000-series chips was developed exclusively for Busicom, and not sold to everyone. Federico called on management to reconsider the terms of the contract. For a technical demonstration, the engineer built a test setup from 4004 for production of 4004. At the same time, instead of the memory of 4001, he installed an EPROM chip that Intel had just invented.

The weak financial performance of the Japanese partners also helped. In one of his phone conversations with Fagin, Seema mentioned that Busicom would not be able to match the price of the chipset. Armed with this fact, Fagin and Hoff asked Noyce to reduce the price of the chips in exchange for waiving the exclusivity clause. By May 1971, permission was granted to sell the 4004 to other companies as long as the product being created was not a calculator. By November, the MCS-4 chipset went on sale.

Board 141-PF. Vintage Calculators Web Museum

It's hard to imagine now, but Intel managers didn't want to focus on the first microprocessor in history, and marketing doubted that it would be easy for sales people to promote such a technically complex device. In another ten years, the company will have a significantly different core area of activity.

Intel launched to enter the nascent market for semiconductor memory, a promising data storage technology tipped to replace magnetic core memory. The 1103 dynamic random access memory chip brought Intel financial success, and due to this, the company went public in 1971. Only in the mid-eighties did the dumping of Japanese manufacturers forced Intel abandon the memory direction.

However, at this stage, little attention was paid to processors. How asserts Fagin himself, Intel produced microprocessors, but in order to sell more memory.

In the following years, Fagin oversaw the creation of the 8008 for the Datapoint 2200 terminal, and then sketched out the architecture and design of the future 8080. In early 1972, Federico launched a work visa for Sima. Around the same time, Fagin came to his superiors with a proposal to urgently move forward with the 8080 project.

Federico was refused: management was intimidated by a chip with 40 legs, while Intel had barely mastered 24. In addition, the managers wanted to first assess the market reaction to the 4004 and 8008.

In principle, the fears are understandable. The 141-PF calculator itself turned out to be financially insolvent: the cheaper Busicom 121-PK performed the same functions, since it worked on Mostek MK6018 and MK6019 chips. In addition, in the Mostek MK6010 the calculator fit on one chip. What if the new microprocessors do not justify themselves financially?

Here, the Busicom Junior calculator (sold in the US as the NCR 18-15) has had its case removed to reveal a single Mostek MK6010 integrated circuit. On photos from a different angle It is noticeable that the chip was manufactured in the 25th week of 1971

Six months later, in mid-1972, Fagin nevertheless pushed his idea, but with cunning: on behalf of Hoffa and Mazor. How remembers Fagin, Intel has lost 9 months of its lead over the rest of the semiconductor industry. The competitors were not asleep: by that time Rockwell had already released PPS-4, similar to 4004; Texas Instruments announced its microprocessor.

8080 is ready only at the beginning of 1974. By the middle of the year it comes out 6800 from Motorola with externally similar characteristics. Fortunately for Intel, the competitor for the 8080 turned out to be large and slow, albeit with a good architecture. Other companies lagged even further behind. It was not until 1975 that Fairchild began selling the microprocessor F8and MOS released 6502.

Following the 1973–1974 oil embargo recession, Intel's stock market price collapsed from $72 to $18. Layoffs began inside, they got rid of about 10% personnel, the processor marketing department was reorganized. Difficulties within Intel and sluggish interest in microprocessors forced Fagin to seriously think about his own company. An idea that he discussed in a private conversation with the head of the microprocessor department, Ralf Ungermann, and found complete understanding with him.

Another possible reason for Federico's departure from Intel is teetering on the edge of speculation. Approved, that during his years at Fairchild, Fagin developed buried contact technology, and his manager went to Intel and patented this invention there. It is possible that there was a small professional conflict.

It is known for sure that Intel belittles any role of defectors-zaylogovtsev. In press materials, the company tries not to mention Hajin and Sima, and in interviews Mazor and Hoff use the streamlined wording “project team” instead of names.

The Intel Museum names Ted Hoffa as the inventor of the microprocessor, without mentioning Federico Faggin or Masatoshi Shima. Intel4004.com

October 31, 1974 was Federico's last day at Intel. Fagin and Ungermann soon founded their own company. Federico headed the new enterprise. The efforts of well-known specialists were noticed by a journalist from the specialized newspaper Electronic News and described in a note what promised the attention of investors. In February 1975, Masatoshi Shima left Intel to join Federico.

It may seem that we already know everything else, and Zilog simply made a legendary microprocessor. In reality, everything is not so simple.

The name of the company did not come immediately. Ralph and Federico spent a long time coming up with the name of the organization, looking through various Electronic Semiconductor or Integrated. Each time it turned out that the name was so uninteresting that it was forgotten the very next day. At some point in the chain of associations they moved from Integrated Logic to I-Log, then to Zilog. The prefix from the last letter of the Latin alphabet implies: the company will show the last word in logic on integrated circuits.

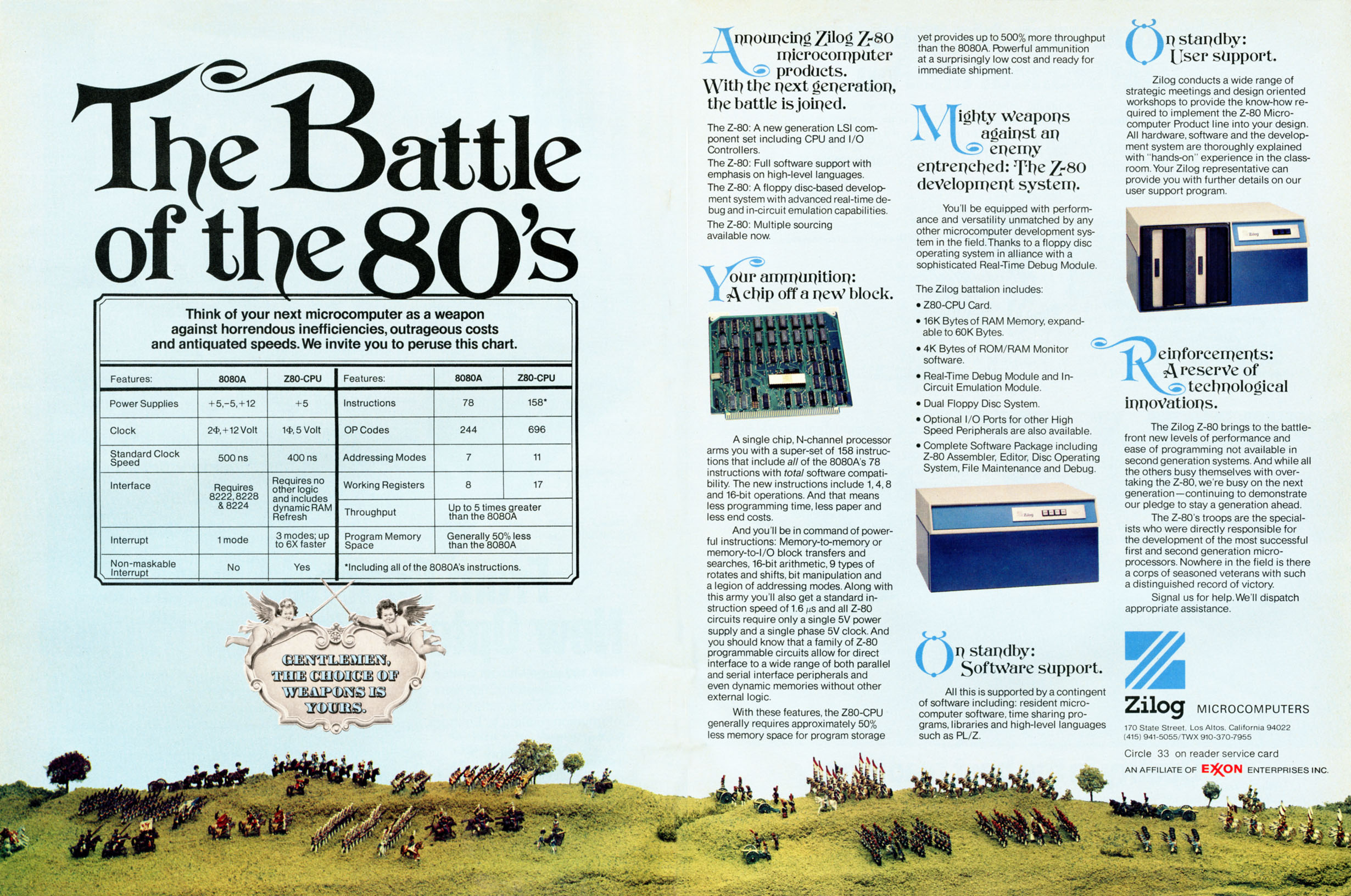

Likewise, the Z80 itself was called differently in the early stages: Super 80. The original name hints that the new microprocessor is a modification of the 8080. There was something to improve. Even to power the 8080, −5 V, +5 V and 12 V were required, and the Zilog processor was planned to have only a +5 V bus. Intel itself released a similar update to the 8080 in March 1976 under the name 8085. However, how remembers Federico, the 8085 was not much competition for the Z80.

At first, Ungermann and Fagin were located in an office on State Street in Los Altos. The company's own office building would appear later, and no factory for production was planned at all. The startup Zilog was conceived as a factoryless company, without production facilities. Fagin chose Synertek to produce the chips and began negotiations.

Soon the contact was broken: the president of Synertek suddenly demanded a license from the second supplier, that is, permission to manufacture the Zilog product. Federico did not want to put up with this, so the first Z80 was produced in the factories of Mostek, another company with five-volt process capacities.

Not only is it difficult to raise money after the recession, there was little available venture capital funding throughout the market. The total amount of investment in high technology in 1975 in the United States was $10 million – a tiny amount compared to several years of injections of hundreds of millions. Luckily, the Electronic News article did help find investors.

In June 1975, they managed to receive the first $500 thousand from Exxon Enterprises, a subsidiary of Exxon Mobil, but on the condition that only $400 thousand of the amount would be spent and that a working processor would be released on March 9 of the following year. Even after accounting for inflation, half a million in 1975 dollars is $2.79 million today.

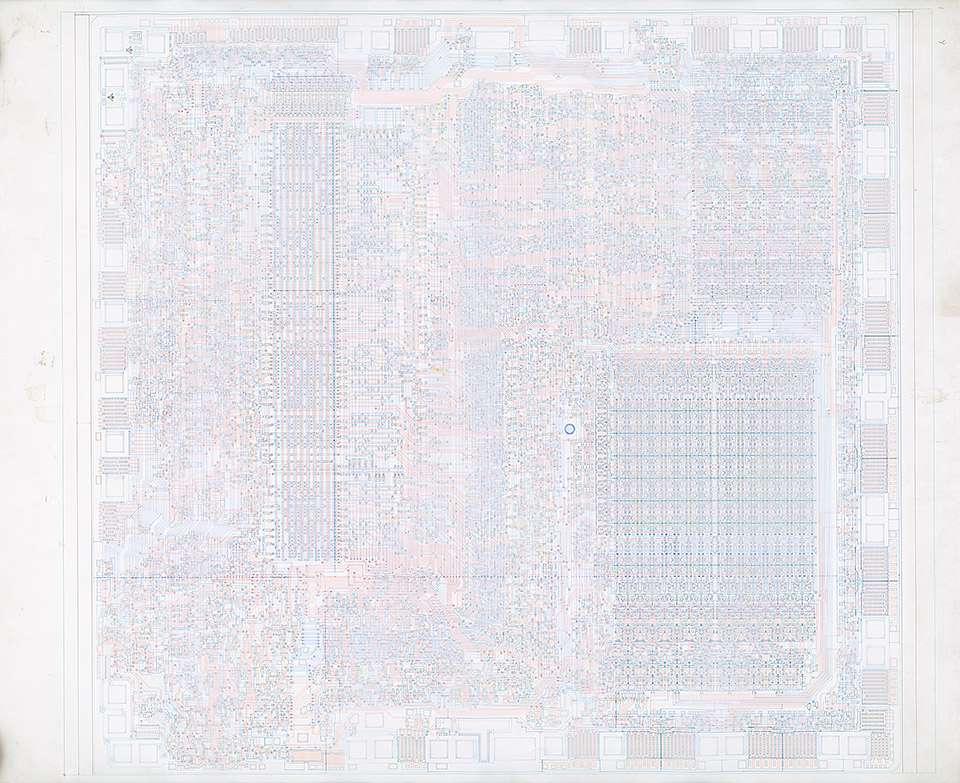

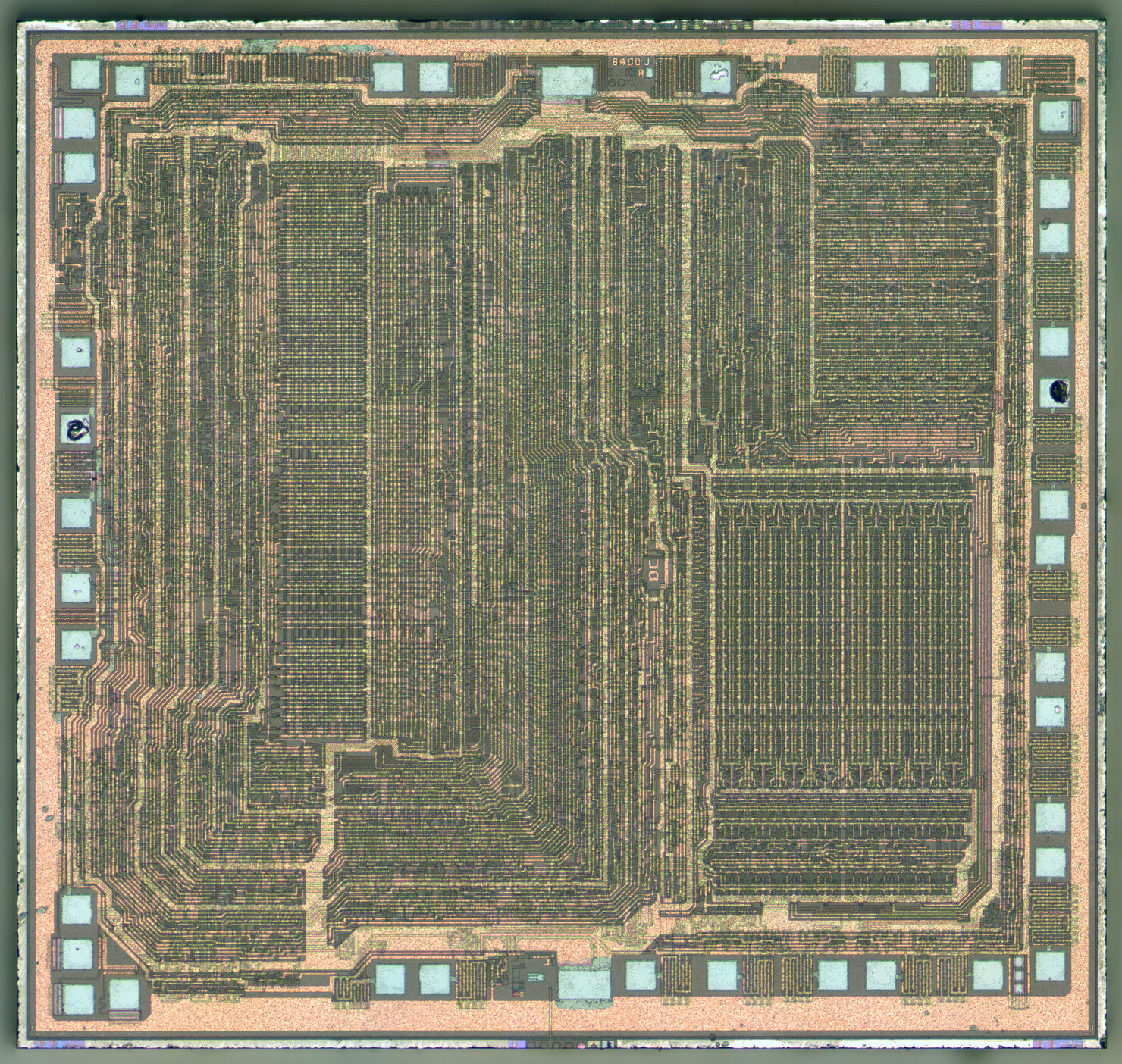

This drawing shows all the layers of the Z80 mask at a scale of 200:1. For several weeks, Masatoshi Shima used a drawing tool to check the correct arrangement of the components so that between all of the 8.5 thousand transistors there was a space dictated by the requirements of the technical process. Computer History Museum

The next few months will be hard work. Fagin claims he spent 3.5 months working 80 hours a week. The two draftsmen worked slowly, so Federico personally supervised them and drew at least two-thirds of the chip himself.

In general, computer-aided design systems for creating integrated circuits began to be used only in the early eighties. Even the 1979 Z8000 was hand-drawn by the Zailologists.

Sima designed the Z80 logic, but Fagin described the overall design of the chip. Ungermann and other employees developed the system and software. Most of the work on the processor was carried out by only 11 people.

The project began in mid-February 1975. The basic design was ready in April, and the hardware architecture was prepared from the beginning of March to the beginning of May. A design guide was written within a month, but the actual logic design began in the second half of May and lasted six months. Although the Z80 logic was ready on September 16, many small bugs remained. The production of lithographic masks began only in November 1975 and took two months.

Z80 diagram. Computer History Museum

The rush was not just due to the whim of investors. Those who came from Intel were well aware of the legacy they had left for their former employer. It was possible to meet the deadlines and budgets, and on March 9, 1976, the first Z80 samples arrived from the Mostek factory. The official launch took place in July of the same year.

An advertisement in the May 1976 issue of Electronics magazine directly compared the Zilog Z80 to the Intel 8080A. Electronics

Even before sales of its first processor began, Zilog put forward an offer to Exxon Enterprises to invest in the company's production capacity and lured Len Perham from AMD to manage the future plant. By January 1977, Zilog launched its own facilities, where the brand new Z80s were riveted.

The 8-bit Z80 has a 16-bit address bus, so it addresses up to 65,536 bytes. It is often said that the Z80 is binary compatible with the 8080. For example, the CP/M operating system runs on both the 8080 and the Z80. Description of the differences and features of the work takes up several pages.

General diagram of the Z80 architecture. Wikipedia user's work Appaloosa. Probably redrawn from page 65 of the book Programming the Z80

Another source of inspiration is the Motorola 6800 and the somewhat similar 6800 NEC minicomputer that Masatoshi Shima used in Japan. That is why the interrupt modes were improved, new index registers and more 16-bit operations were added.

Photo of die Z0840004PSC, later model produced in 1990. ZeptoBars

The Z80 was one of the most common processors of the desktop computer boom of the early eighties. The only person that can compete with him in popularity is MOS Technology 6502. Worked on Z80 Osborne 1, TRS-80, ZX Spectrum And dozens of others.

The Z80 was installed in advanced typewriters and word processors, video game consoles and slot machines, calculators and telephones, as well as a variety of embedded systems, from traffic lights to automatic doors. One of the best indicators of processor quality is the number of clones and derivatives. The Z80 was copied in Japan, China, Germany and the Soviet Union.

Ralph Ungermann retired from Zilog in 1978. In 1980, Zilog's first head, Federico Fagin, left the company; he later founded Cygnet Technologies and Synaptics. Masatoshi Shima returned to Japan, where he opened the Intel Japan Design Center and VM Technology Corporation. Zilog itself has had several owners.

Subsequent Zilog microprocessors were much less popular, so the company focused on microcontrollers, existing in this form to this day. There were attempts to improve. For example, in 2007 Zilog tried launch 32-bit microcontrollers on ARM, but the idea failed, and the direction had to sell.

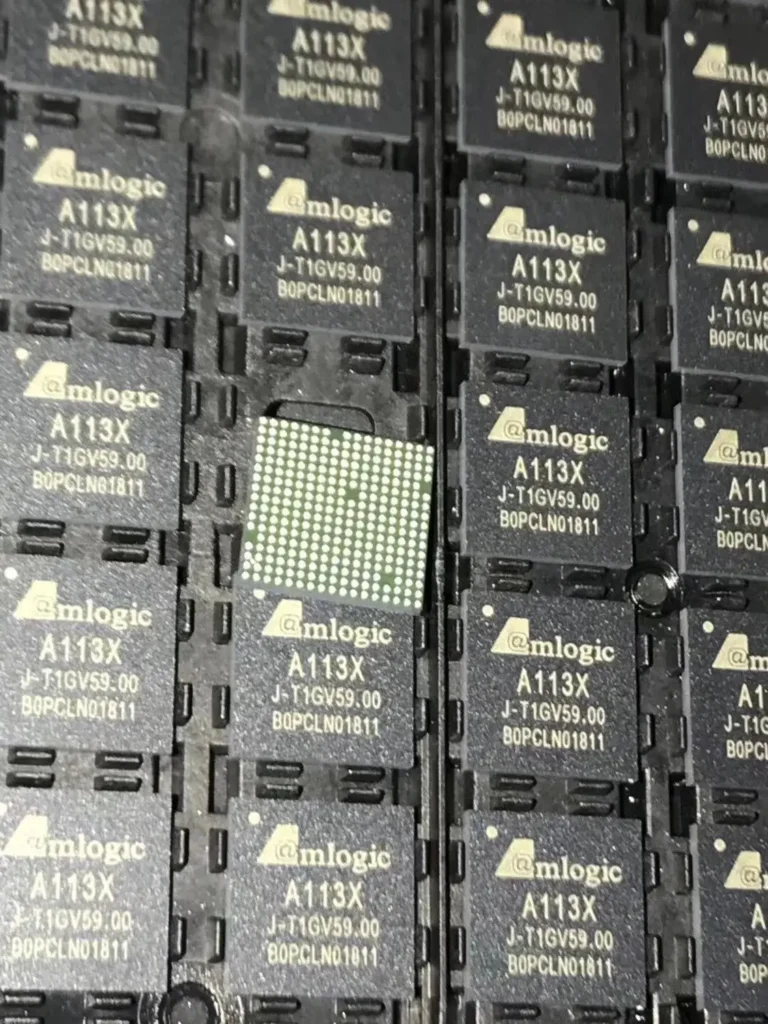

The Z80 microprocessors themselves are still in production. “Centipede” Z80 for sale from $5.5 to $9.75 and recommended as a replacement for a failed ZX Spectrum chip. Although the case gives the chip the appearance of a guest from the seventies, the maximum operating frequency of modern Z80 varies from 6 to 20 MHz – much higher than the original frequency of 2 MHz and 4 MHz considered the norm in the eighties. Enthusiasts continue to release software for the Z80 to this day.

Z80 with 40th week 2016 date stamp. TFW8b.com

However, recently, on April 15, 2024, Zilog announced end date for sales of almost the entire line of models Z84C00. The original Z80 is being discontinued.

This does not mean that the Z80 can only be emulated on FPGA. Sale continues eZ80, chips with full binary compatibility with the Z80. The eZ80 processor is not only up to four times faster than the original at the same frequency, but also reaches speeds of up to 50 MHz. It is the eZ80 that is installed in some Texas Instruments calculators.

But the original Z80 can only be purchased until June 14, 2024. The sales start date and the last opportunity to buy a regular Z80 are separated by almost 48 years. Few devices can boast of such relevance.