war of systems before the advent of iOS and Android

The first system for processing large amounts of data appeared at the end of the 19th century. American engineer Herman Hollerith created it in order to process the results of the US census. Hollerith's company, the first IT startup, found private investors and government contracts, created a new industry, and attracted hundreds of clients. However, its monopoly position in this market was short-lived – a competitor soon appeared who was able to offer users lower prices and new technologies.

Anton Basov, a researcher of the history of science and technology and the author of the Center for Continuing Education at the Faculty of Computer Science at the National Research University Higher School of Economics, talks about the first war of systems in the history of IT.

How to become the first monopolist in the data processing market

The U.S. Constitution requires that a “count of the actual population of the States” be made every ten years. The first census of the former thirteen colonies took place in 1790. Since then, the American population has grown and counting has become increasingly difficult. The processing of the 1880 census took eight years and ended shortly before the new census was taken. It became clear that counting the population manually was no longer possible.

Two people took up the issue of mechanizing the census: John Shaw Billings and Herman Hollerith. Billings was an extremely versatile person: a surgeon by training, he became one of the chief doctors of the American army, played an important role in the creation of the Johns Hopkins Hospital at the university of the same name and the New York Public Library. As a representative of the US Army Medical Director, Billings participated in the analysis of data from the 1870 and 1880 censuses.

It was while working on the 1880 Census that Billings met Census Bureau employee Herman Hollerith. Hollerith, a recent graduate of the Columbia School of Mines, worked for the Bureau on the statistics of industrial machinery.

The work of enumerators at the Census Bureau was tedious. Apparently, while watching her, Billings said to Hollerith: “There must be some kind of machine to do this mechanical work.”

Hollerith was fired up with an idea. After some time, he showed Billings a model of a calculating machine. The two spent a lot of time trying to improve the system until Billings got bored – he was a doctor, after all, not a mechanic. However, he accomplished the main task – he interested Hollerith in the question and even outlined a solution: each unit of data is recorded using perforations on a separate card, which is then processed using special devices.

In 1884, Hollerith retired from the Census Bureau and filed his first patent application. By 1889 he received three patents – US395 781, US395 782, US395 783 – which describe all parts of its system:

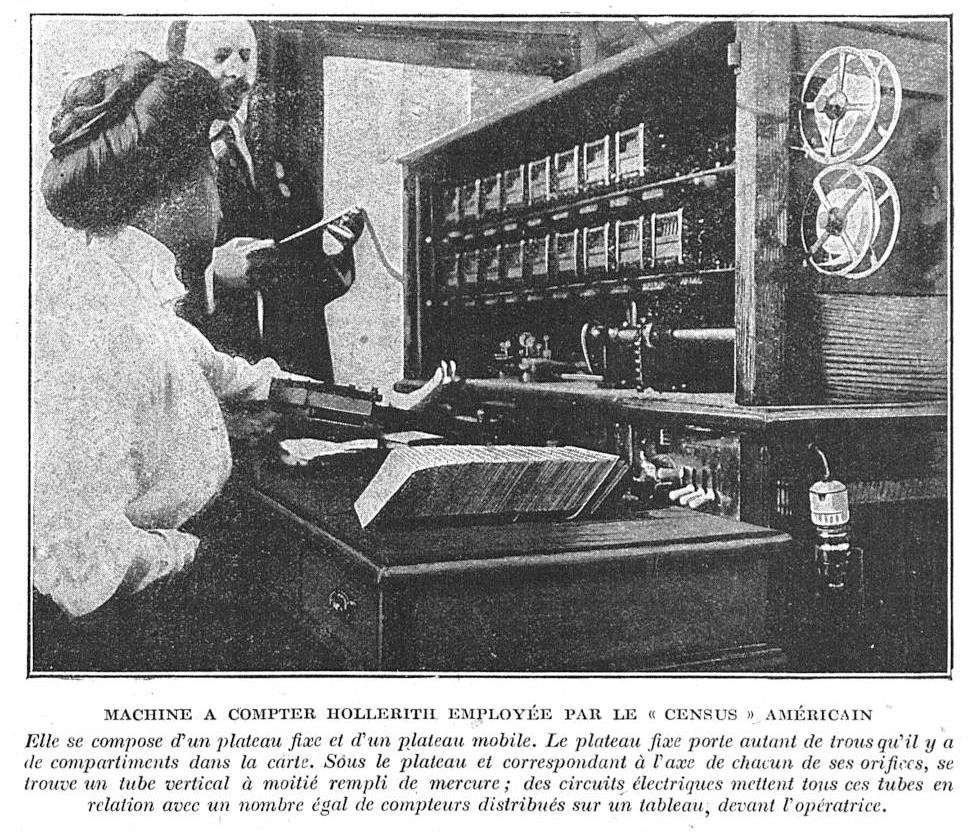

Data is entered onto cards using a punch. Each hole corresponds to the presence of some characteristic – gender, age, skin color.

The operator passes the cards through the tabulator. When there is a hole in a certain place on the card, it allows you to close the electrical circuit and add one to the counter. Thus, each counter counts the number of cards that have one or another attribute.

When the card is read, one of the cells of the sorting box is automatically opened, where the card is placed (the sorting box can only sort within one attribute, for example, by age: up to one year, from 1 to 10 years, from 11 to 20, and so on).

Punched cards can be passed through the tabulator again and again, sorting them according to different characteristics and their combinations.

Like any tech startup founder, Hollerith has been looking for sponsors and clients with varying degrees of success. In 1886, he received his first major contract – his system was used to analyze demographic statistics in Baltimore. Tests followed in New Jersey and New York, as well as in the office of the US Army Medical Director. Most likely, Hollerith received all these contracts not without the support of Billings.

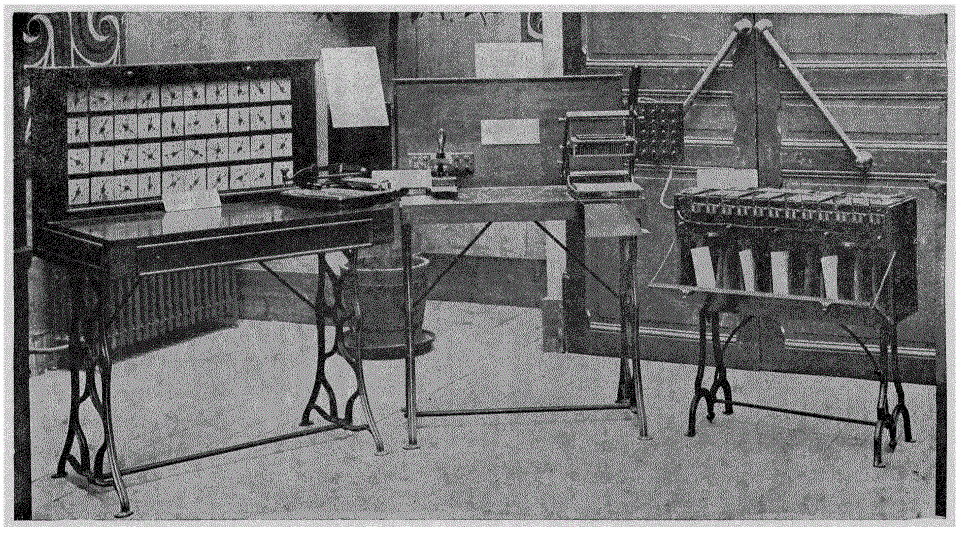

In 1889, Hollerith sent a set of equipment for processing punched cards to the World Exhibition in Paris, where it was awarded a gold medal. At the same time, the Census Bureau announced a competition for systems for processing 1890 census data. Hollerith's system wins and he signs a contract for the supply of equipment.

The speed of the system was enormous for that time. The first results were published six weeks after census day. In total, processing the results of the 1890 census took three years (versus eight for the 1880 census). Using the Hollerith system saved about five million dollars out of a total census cost of about 12 million.

Hollerith decided not to sell the Census Bureau equipment but to lease it. After processing the data, the machines returned to him and he began looking for other clients. Hollerith was able to sell the new technology to two customers – foreign governments and big business. On the one hand, his machines began to be used for population censuses in Austria, Canada, Italy, Russia and other countries. On the other hand, Hollerith began to introduce calculating and analytical machines for working with punched cards in insurance companies, railroads and other enterprises where it was necessary to quickly and efficiently process large amounts of information.

How the US government decided to “enter IT”

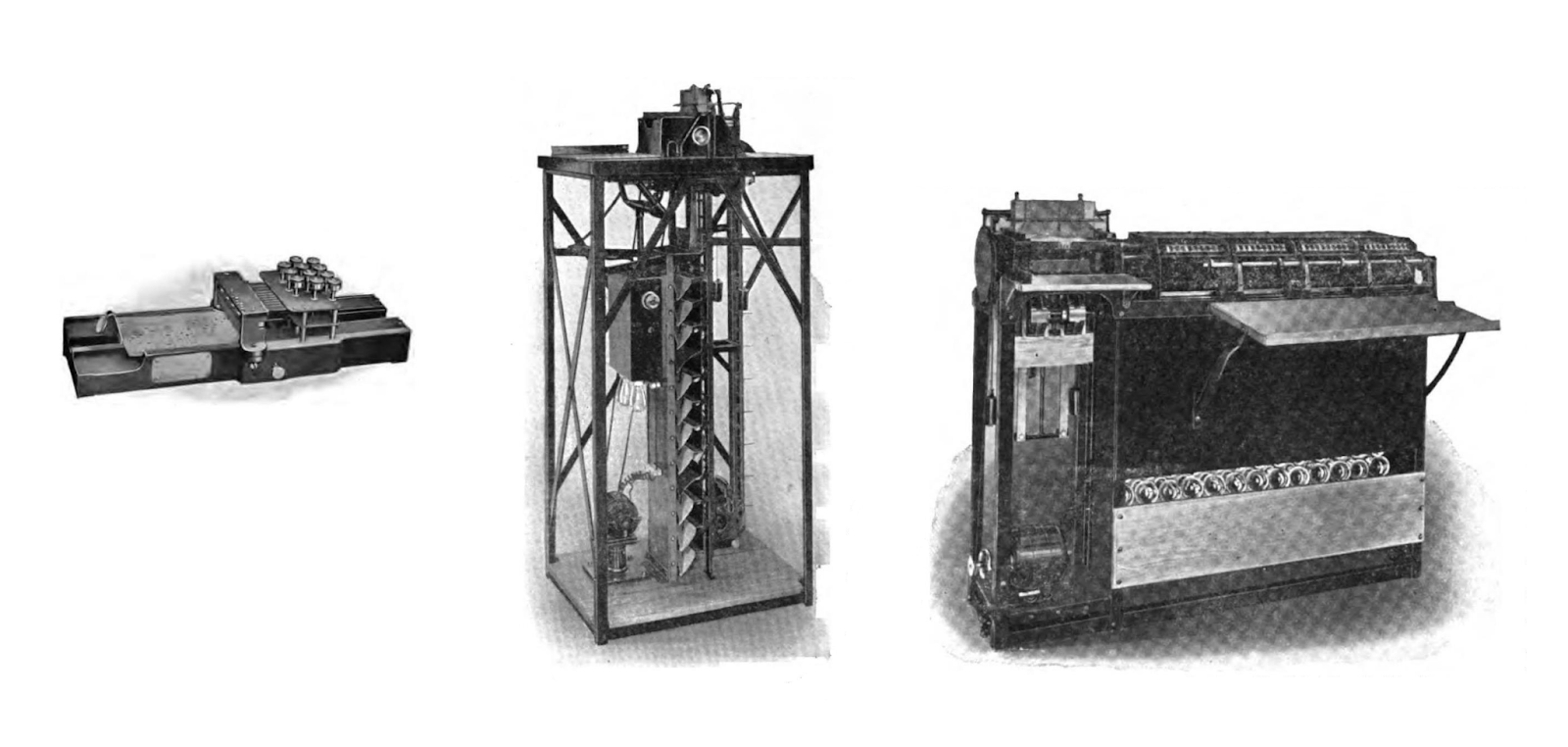

When preparing the 1900 census, there was no doubt whether to use the Hollerith system. Hollerith offered the Census Bureau improved equipment: a tabulator with automatic card reading (previously cards were read one at a time on a manual press), an automatic sorting machine instead of a sorting box, a new punch.

However, the aftermath of the 1900 census marked the end of Hollerith's monopoly on the supply of punch card equipment. A permanent Census Bureau was established in 1902, and statistician Simon North became its director in 1903. After examining the contracts with Hollerith, North comes to the conclusion that the rent is too high. Hollerith refuses to make concessions, and the Bureau does not renegotiate the treaty. Instead, North creates his own machine shop at the Census Bureau.

The workshop's task was to create its own equipment. There was plenty of time before the next census, and Hollerith's first patents were already expiring – so the workshop could simply copy his old machines and make minor improvements to them. The workshop employees started with this, gradually moving on to the development of new, more advanced equipment.

Hollerith tabulators, even with automatic punch card entry, had a problem – data from the cards was not recorded, but only displayed on the counters. They had to be rewritten manually, which was tedious and led to errors. By 1907, the Bureau's workshop had developed the first printing tabulator.

Another problem with the census was punching cards, that is, punching holes in them. It seems easy to punch a hole in a piece of paper, but try doing it several thousand (or even tens of thousands) times a day, and making sure the holes are only in the right places. Although Hollerith punchers helped to punch a hole in the right place on the card, they required a lot of physical effort from the operator.

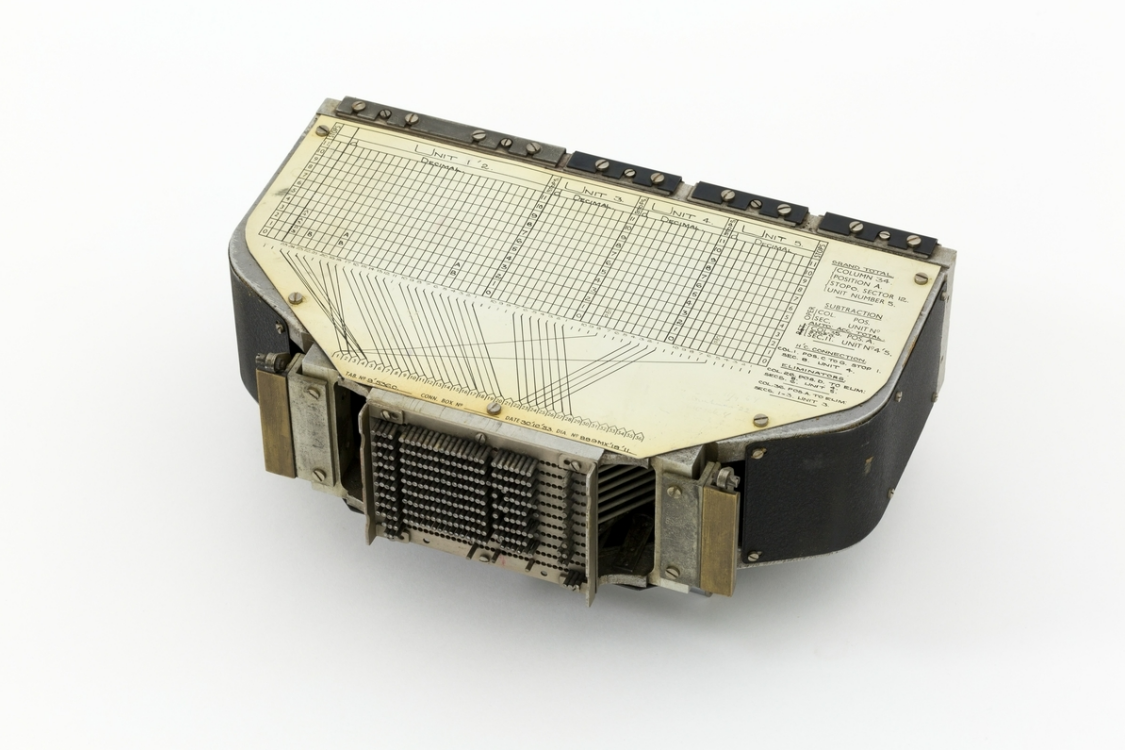

For the 1910 census, workshop employee James Legrand Powers offers a new design puncher – with automatic feeding of punched cards, a convenient keyboard and an electric motor for punching holes. Powers, a talented engineer and inventor, had a hand in many of the Census Bureau's workshop developments and received several patents.

Powers can rightfully be considered one of the pioneers of the IT industry. Despite this, he is completely forgotten, and numerous holes gape in his biography. Little is known for sure: Powers was born in 1871 in Odessa. In 1889 he moved to the United States and worked as a mechanic for large companies, including Western Electric.

It is unknown when exactly he became a member of the Census Bureau workshop, but he certainly worked there between 1907 and 1911. Apparently, the US government gave him permission to patent his inventions, even though they were made by him in government service.

During the 1910 census, all the equipment then available was collected. Both new Powers punches and old Hollerith punches were used to punch the cards. The sorting machines were also Hollerith, built by him for the 1900 census and heavily modified (Hollerith himself, having learned about the modification of his machines, sued for violation of his patent. As a result – an unexpected turn – the court revoked the patent, since Hollerith first built the sorting machines for the Census Bureau, and only then patented them). But the tabulators were already developed by the Bureau’s workshop. Despite this motley mixture, the census was successful.

However, already by the 1920 census it became clear that it would still not be possible to manage with the help of a workshop alone. During subsequent censuses, the Bureau returned to the practice of renting or purchasing equipment that it did not make sense to manufacture in-house. Other government agencies also rented or purchased equipment rather than making it themselves (for example, the Postal Service used equipment from both Hollerith and Powers).

Who won the first standards war?

In 1911, two important events occurred in the punch card industry.

Firstly, Tabulating Machine Company Hollerita merged with three other companies into a holding company Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company. Hollerith sold a controlling stake and became a consultant in the new company. In 1915, Thomas Watson Sr. became president of the company, who held this post until 1956.

Second, James Powers left the Census Bureau workshop and established Powers Tabulating (since 1914 – Accounting) Machine Company.

So, two competing companies appeared in the punch card processing equipment market. Why exactly this event can be considered the beginning of the first systems war in the history of IT? It's all about patents. Powers could not use Hollerith's work (yes, the life of the first patents had already expired, but both the sorting machine and the automatic card entry into the tabulator were still protected), and therefore was forced to invent his own solutions.

All Hollerith machines were based on the principle of electrical reading of punched cards: a hole in the card allows the contacts to close and activate one or another mechanism. Powers decided not to try to circumvent Hollerith's decision, but simply to replace electricity with mechanics. In the sorting machines and tabulators he developed, the reading mechanism resembled a typewriter or adding machine: spring-loaded pins were lowered onto the card; where there were holes in it, the pins passed through and activated the counting or printing mechanisms.

By 1914, Powers was offering a set of four machines for processing punched cards: a puncher, a newly invented punch checker, a sorting machine, and a printing tabulator. From a technical point of view, his equipment was more advanced than that of Computing-Tabulating-Recordingwhich offered customers three machines – a keyless punch without a motor, a sorter and a tabulator with counters.

However Computing-Tabulating-Recording I wasn't going to give up. To begin with, they imposed Powers Accounting Machine Company tribute: in 1914, Powers had to buy a license to use the patents in exchange for 25% of the proceeds from the rental of machines and 18% of the proceeds from the sale of punched cards. It is not entirely clear which patents Computing-Tabulating-Recording could use Powers; Apparently, he feared costly lawsuits that would undermine the company's already weak finances.

Hollerith's bet on business also worked. He began supplying his equipment to private companies back in 1890, at the same time as the then census. Twenty-five years later Computing-Tabulating-Recording there were already 550 customers using 1,076 tabulators and 827 sorting machines to process 660 million punched cards per year. Powers, a good engineer but a bad entrepreneur, could not boast of such figures. By 1918, he was tired of commercial troubles and left the company he founded, the new head of which was engineer William Lasker.

Although Herman Hollerith and James Powers retired, their companies continued to grow. America's entry into World War I gave business a new impetus – the government needed systems to process data on soldiers at the front and the economic situation on the home front. After the war, this trend continued – the task of processing census data faded into the background, and computing machines began to be used for a variety of tasks, from accounting to plant classification.

In 1924 Computing-Tabulating-Recording changed the name to International Business Machines. And in 1927 Powers Accounting Machine Company merged with seven other companies in Remington Rand.

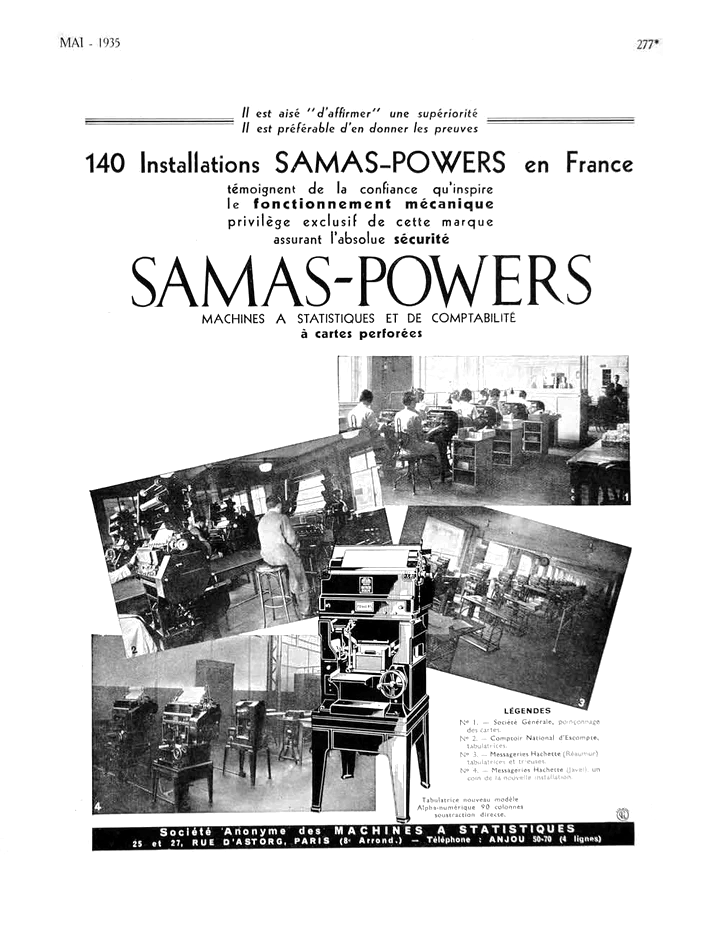

Even before the war, both companies had divisions in Great Britain, France, and Germany. In 1929, the British and French offices of Powers' company merged under the name Powers-Samas (or Samas-Powersfrom French Société Anonyme des Machines à Statistiques). It's funny that Powers, completely forgotten as a person, continued to live in the company name until the 1950s, not only in Europe, but throughout the British Commonwealth.

At the end of this historical analysis, let’s try to answer the question – who actually won the first systems war in the history of IT? Apparently it ended in a draw. It was competition that forced the Hollerith and Powers companies to continue to improve their products and create innovations – first in the field of computers and then in computers. It is significant that the US Census Bureau, where this whole story began, used products from both companies: before World War II, IBM equipment; and then, in 1952, the Bureau purchased its first computer – UNIVAC I – from Remington Rand.

Companies founded more than a hundred years ago continue to operate today – IBM itself, and Remington Rand – as part of the company Unisys.