practical example of an attack using the .zip domain

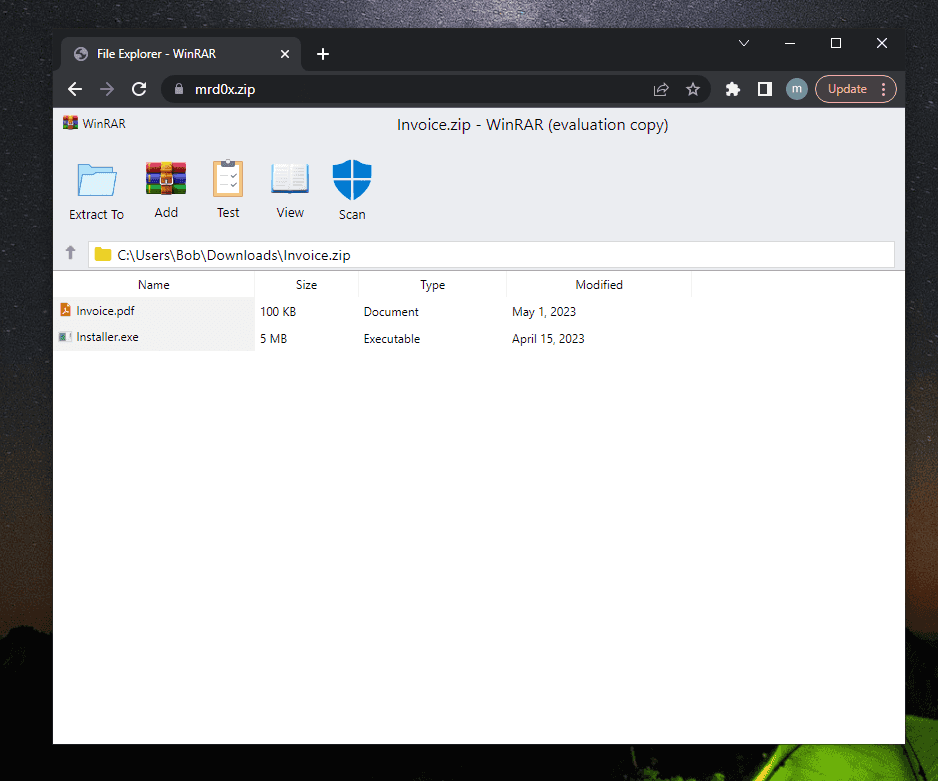

What such an attack might look like in practice last week showed researcher known as mrd0x. He registered a domain name mrd0x.zipon which I reproduced in detail the interface of the WinRAR archiver.

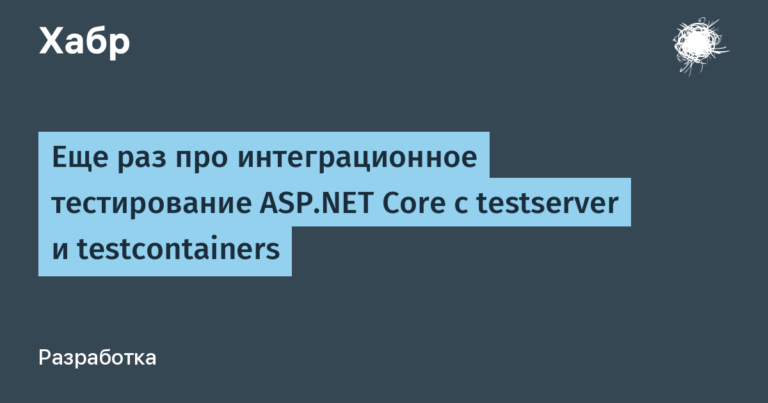

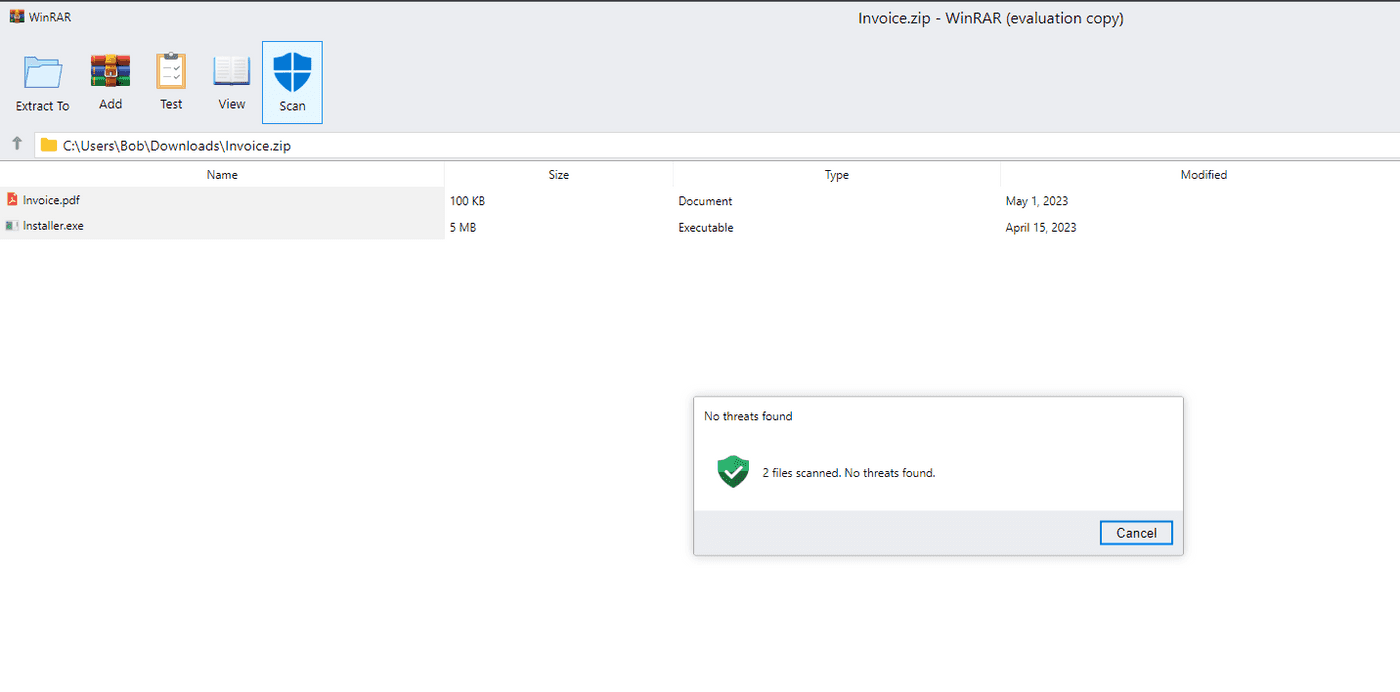

An obvious attack scenario is as follows: an attacker registers a domain (or several domains) that looks like a filename. He sends links to them to victims via instant messengers, inserts them into junk websites on the Web, and sends them in bulk by mail. By clicking on the link, the user sees a seemingly ordinary archiver window, where you can allegedly “unpack” some files. mrd0x also showcased some “user experience improvements”, such as adding a message that files were allegedly scanned for threats:

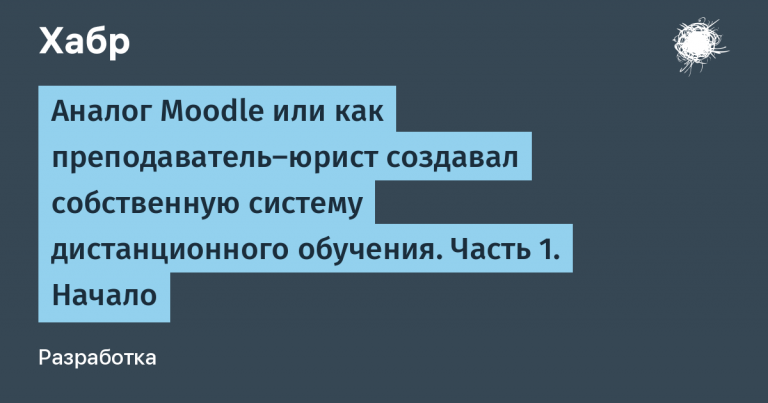

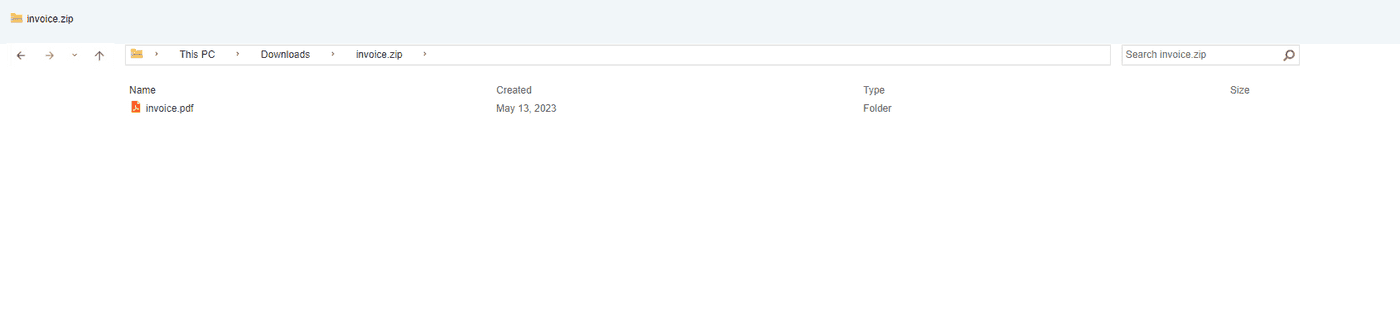

It is not necessary to emulate in the WinRAR browser, you can reproduce an even more familiar Windows Explorer window:

By clicking on a file or on the “Extract to” button in the “archiver”, a file will be downloaded, which the potential victim must open without any doubt – it is also “checked” or even looks like it is being launched locally. But there are other options when the victim is redirected to a phishing page, for example, a cloud service, where they are asked to enter the username and password for their account. It is clear that such an attack will work with people who have difficulty distinguishing a real program from a browser. But such people are not so few. The screenshots above show the ideal view of the pseudo-archiver, and if you expand the browser window to full screen, the interface also stretches and looks suspicious.

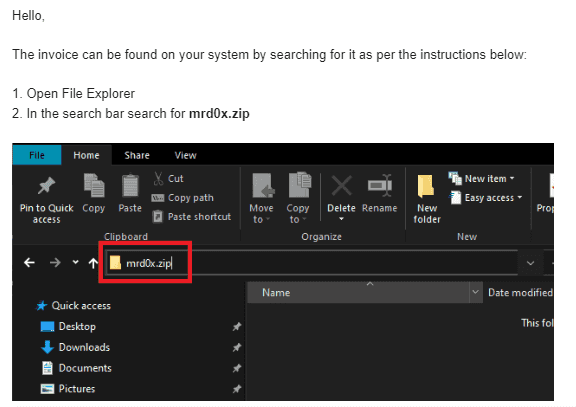

It seems that such an attack is not much different from any other attack using any domain. With one exception: links that look like filenames will be active. For example, Twitter already automatically makes mrd0x.zip an active link, as does the Telegram messenger. Malicious domains in the .zip and .mov zones will be a little easier to hit, which means that there will be a few percent more successful hacks. Mrd0x showed the most interesting problem using Windows Explorer (the real one) as an example. If you enter a file name in Explorer that is not in the open folder, Windows will try to open the site with the same URL in the browser.

Google’s desire to make a few extra dollars off domain names is understandable, but such an intrusion into the decades-old division between “web” and “files” is hardly a good idea.

What else happened:

Published detailed study about voice attacks in which the command is transmitted at extremely high frequencies (from 16 kilohertz and above). We wrote about this work in March, when examples of attacks had just appeared. The microphones of modern devices easily recognize voice commands transmitted at the upper end of the audio frequency range, while the owners of smartphones and smart speakers almost certainly do not hear such commands. The full text of the study provides many new details, such as the effectiveness of the attack using different audio compression methods or the practical distance from the attacking device to the attacked. An obvious means of combating such attacks has also been proposed: on the receiving device, you can simply filter the sound above a certain frequency. This will not affect real voice commands in any way, and attempts to covertly order something to the home device are guaranteed to neutralize.

In a recent study by ESET, described malicious functionality of an Android application. The screen recording app initially did not have any malicious add-ons, but at some point a backdoor arrived along with the usual update. It allowed tracking the coordinates of the victim, recording sound from a microphone, and uploading arbitrary files to the command and control server.

Zyxel Company closed two critical vulnerabilities in hardware firewalls and VPN devices.