how a mechanical pencil influenced the formation of an electronics giant

The mechanical pencil is well known throughout the world, largely thanks to the founder of Sharp, Tokuji Hayakawa. An enterprising craftsman took an idea from an existing device and revolutionized one of the most convenient writing instruments in the world. He went from an apprentice to a successful businessman, survived the loss of his business and family in a major earthquake, started everything almost from scratch and achieved success again, becoming one of the pillars of the Japanese economic miracle of the second half of the twentieth century.

Japanese spirit: take what is known and improve it

Tokuji Hayakawa was one of those restless autodidacts who were so disliked by the conservative industrialists of Japan – an upstart, carried away by new dubious trends, without a name, capital or connections. From the age of nine, Hayakawa worked as an apprentice in the shop of a master ironmonger who made and sold traditional Japanese jewelry for women – combs and hairpins.

Hayakawa's talent was revealed when he made a special buckle that did not require holes in the belt. According to legend, he came up with it after watching enough Westerns in silent cinema. Japanese society at the beginning of the twentieth century was just beginning to adopt Western clothing habits, and Hayakawa’s invention came in handy – the buckle became very popular. The master advised Tokuji to patent the invention. So Hayakawa became the owner of his first patent – for the “Tokubidze” buckle (the name is a play on his name, literally “Toku buckle” – the first hieroglyph is taken from the author’s name – ?)

There were so many orders for the buckle that Hayakawa decided to open his own workshop. Having completed his apprenticeship with a master in 1909, he was already a full-fledged artisan, and in September 1912 he became an independent businessman (this date is usually considered the beginning of the Sharp Corporation). Tokuji understood that the buckle's success could be fleeting, and looked for new ways to apply his talent. After some time, he came up with a hoop for Japanese umbrellas, a convenient sliding sleeve, which he also patented.

The demand for his buckle was high, and to keep up with the flow of orders, Hayakawa built a factory, hired workers, and after some time equipped the production with an electric generator with a capacity of 1 horsepower. Driven by the motto “Take initiative and be first,” he became one of the first Japanese businessmen to mechanize production.

Mechanical pencil: almost a family business

Tokuji grew up in the foster family of Ideno, where his parents sent him due to their poor situation, and, accordingly, was forced to bear this surname. He learned the truth as an adult, and at some point restored contact with his relatives – brother and sister. By versions Sharp chroniclers, it was the older brother who brought a new stream of orders into the metal business – for the manufacture of mechanical pencil parts. Tokuji was dissatisfied neither with the appearance of the pencils then in use, nor with the fact that he only had to produce part of the mechanism. The pencil, as a rule, had a thick celluloid shell, but was also very fragile – no more than an expensive toy.

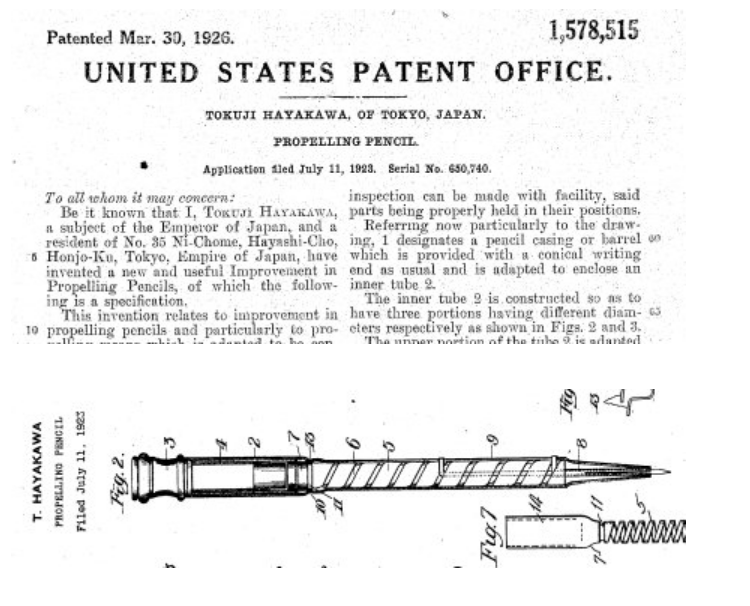

Using his knowledge of metallurgy, Tokuji improved the design and appearance of the pencil by making the shell out of nickel, and in 1915 he patented the “Hayakawa Mechanical Pencil”. That same year, he was legally granted the right to reclaim his family's surname, and together with his newfound brother, they founded the Hayakawa Brothers' Metal Stationery Works.

Initially, the pencil was not very popular – the metal case, made of nickel, was cold on the fingers and did not look good with a kimono, but Hayakawa continued to replenish supplies and one day received a large order from a company located in the port city of Yokohama. It turned out that his pencils became very popular in the West. Japanese businessmen sensed the export potential of the product and rushed to purchase it directly from the Hayakawa factory. Under the pressure of orders, he was forced to build a separate factory for the production of pencils.

Surpassing analogues

Tokuji was not the inventor of the mechanical pencil, but he made it as convenient as possible.

The first mechanical pencil can be considered a device invented in 1565 by Conrad Gesner, a naturalist and bibliographer from Switzerland. To sharpen it, the lead had to be adjusted manually.

The first pencil with a mechanism that set the lead in motion was patented in 1822 by Sampson Mordan and John Hawkins in Great Britain. From this time until 1847, more than 160 patents for such pencils were registered. The spring mechanical pencil appeared in 1877, and in 1895 a prototype with a rotating mechanism was already created.

Almost simultaneously with the advent of the mechanical pencil, Tokuji Hayakawa, American businessman and inventor Charles Kieran created his own ratcheting pencil, which he called Eversharp. He used a slightly different strategy for patenting – claiming individuality, he did test marketing in stores, and then filed for a patent. His pencils were also very popular, but Kieran himself, as a result of poorly chosen partners, eventually went out of business.

As for Hayakawa, he continued to work on improving the pencil. In 1916, he developed a mechanism for pushing the lead through a simple press, and in this form the pencil exists to this day. The final product was called the Eversharp Pencil, from which the Sharp Corporation would later take its name.

Shock of foundations and rebirth

On September 1, 1923, an incident occurred in Sagami Bay. earthquake magnitude 7.9, which became the most destructive in the history of Japan – it almost completely destroyed Tokyo, Yokohama and eight other cities. The most disappointing thing was that the earthquake did not cause much damage to Hayakawa's factories – but a fire carried by strong winds destroyed everything. Hundreds of thousands of people died. The young businessman himself lost his family in this disaster.

Left with nothing, Tokuji was a refugee for some time. Together with his surviving employees, he moved to a rented apartment. In order to pay off the debts incurred as a result of the pencil supply contract with Nihon Bungu Seizo, Hayakawa was forced to dissolve the Hayakawa Brothers Company and transfer business operations to his partner. He also agreed to hire the remaining employees of this company, and he himself became its chief staff engineer for the next year.

At the end of his consulting work, Tokuji left Nihon Bungu Seizo on fairly good terms and began planning a new life in Osaka. He leased the land and exactly one year after the earthquake, on September 1, 1924, he opened a sign above the new office – Hayakawa Metal Works Institute Co. That same year, he read a newspaper article about radio broadcasting starting in Japan in 1925.

After some time, he went to the Ishihara Clock Shop of his distant relative, where he saw the first crystal radio brought from the USA. Without hesitation, he bought himself one copy and later, together with his employees, he simply took it apart to understand how it worked. None of them knew how electrical circuits worked, but the engineers were confused. On April 1, 1925, the assembly of the first Japanese crystal radio receiver was completed, and on June 1, when radio broadcasting began in Japan (this was done by the JOBK radio station, NHK prototype), the receiver successfully picked up a signal. Hayakawa began producing and selling radios, which were in great demand because they were cheaper than imported products.

What does Hayakawa's story teach us?

To make radio more accessible (crystal receivers required headphones and had poor signal reception), Hayakawa turned his attention to the technology used in tube radios. By 1930, Hayakawa's engineers had developed a unique design for the Sharp Dyne radio with a horn loudspeaker. The device made it possible to catch a higher-quality signal and was much cheaper than its American counterparts – for many Japanese it became synonymous with the word “radio” itself.

When television came to Japan, Hayakawa Electric became the first Japanese company to begin mass production of televisions – in 1951, Hayakawa's engineers presented the first working prototype of a television receiver, and in 1952, his company was the first to enter into a licensing agreement with Radio Corporation of America. However, the first TVs, which had a standard 17-inch screen, were outrageously expensive, and Hayakawa focused on a smaller 14-inch screen that would fit better into Japanese homes. By 1955, Hayakawa Electric was already producing 5,000 televisions per month. The company captured 60% of the new market, and for the Japanese the Sharp brand again became a national symbol of new life.

When the computer era arrived, engineers became obsessed with the idea of creating and selling personal computers. Hayakawa suggested that they focus not on bulky computers, but on more compact and convenient calculators. In 1964, before the start of the Tokyo Olympics, his company released the world's first transistor-diode calculator.

Hayakawa’s company had many more interesting innovations to its credit: the idea of combining a computer and a TV, the world’s first mobile phone with a built-in camera, as well as the world’s first plasma TV with 8K resolution. The entire history of the company's achievements is united by the spirit of innovation set by its founder from the very first inventions.

Afterword: lasting value of a patent

In the 21st century, things got worse for Sharp Corporation, as its founder named it after the famous pencil in 1970. Several times it found itself on the verge of bankruptcy, and in 2016 a controlling stake you bought Chinese shareholders through the Taiwanese company Foxconn, a heavyweight in the patent market.

Japanese business publication Nikkei notesthat the 2020 financial year was successful for Sharp, despite pandemic restrictions – operating profit grew by 62% for the year. No wonder, apparently, that Sharp managers are considering deal with Foxconn as a chance to enter the global market. But Sharp's most valuable asset is still its patents—the leadership of its management company, Foxonn, has always been interested in the monetization of its patent portfolio.

Useful from Online Patent:

→ What is the Register of Domestic Software?

→ Can a foreign company enter its program into the Register of Domestic Software?

→ How IT companies can maintain zero VAT and get included in the Register of Domestic Software