The power of the crowd. As in San Francisco, developed a musocoque robot – river cleaner

If you walk along the banks of the Chicago River this summer, you will see something rather unusual. Among ducks, swans, fish, rare beavers and otters from time to time a small robot will swim. Similar to a small raft, it will be lazy to walk up and down the river, collecting everything that will be on its surface. This is Treshbot – the brainchild of the Chicago-based startup Urban Rivers, which brought together environmentalists, robotics and other professionals to clean up urban rivers from debris and help their inhabitants.

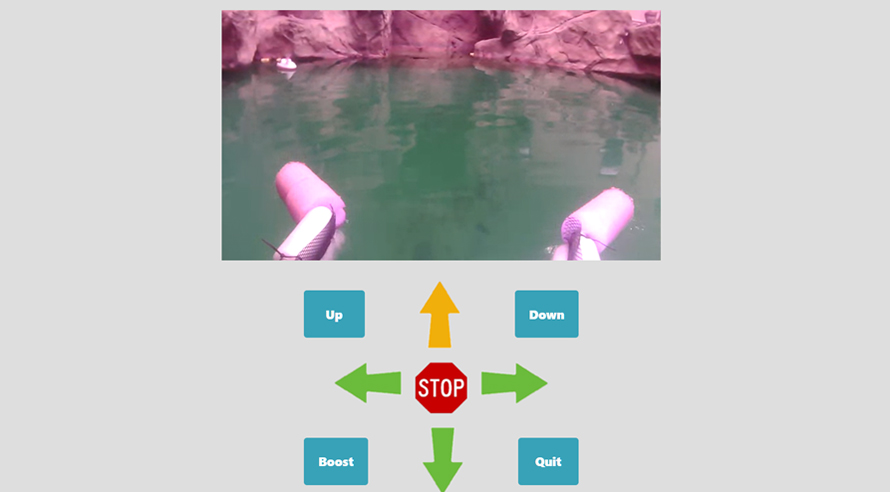

In appearance, the Tashbot may seem like a “water rumba”, autonomously (or accidentally) choosing the path while there is still pollution ahead. He moves by himself, just like a rumba! But actually the opposite is true. The robot does not choose the direction itself; at any moment it can be controlled by one of about 4,383,810,342 people – global Internet users.

Each person with Internet access can log in to the Urban Rivers website and become a bot pilot for two minutes. The company's goal is for the person to find the garbage at that time and manage to grab it, and ideally also take it to a special container by the river, from where it will be removed. So, the purification of rivers becomes not a virtual activity that “someone else is engaged in”, but a very real activity in which you can physically participate – without contaminating your hands.

Nick Wesley, one of the project managers, says:

We are finally at a stage where most people live in places with a decent Internet connection. The technology required to build our robot is as simple as technology in an inexpensive drone. You can stream a video with a rather small delay, and at such speeds it can be controlled. The benefit to nature, interesting for a couple of minutes, gives the feeling that today you have done something useful, what else is needed.

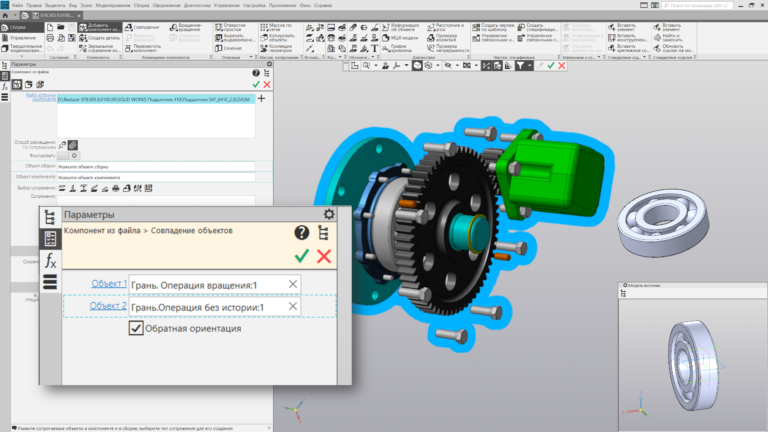

Treshbota Construction

The idea of developing controlled waste bins for the purification of urban rivers appeared two years ago. In June 2017, Urban Rivers successfully created "floating gardens" on the same Chicago river to help animals return to their natural habitat. Unfortunately, the team realized that these gardens were quickly littered with debris. To solve the problem, they began to invite volunteers, who in the old manner went to the river in the mornings and manually collected more or less large litter. Efficiency was very low, mainly because of the irregular flow of the river.

Sometimes people would go to shore in the morning, and there was no garbage to collect. Then something changed in the flow, and soon this place was filled with garbage. We realized that we need a solution that will be included constantly. So that trash can be cleaned in real time as it drifts.

The rudiments of ideas appeared, but the team did not know how to make the robot find and collect pollution. Computer vision and image recognition technologies have progressed well in recent years, but it still wasn't easy to teach a bot to determine what fits the concept of "junk". “Garbage” is a rather abstract concept. It turned out that it is good to separate it from natural objects in the river so far only people can. Thus, the idea of creating a remotely controlled "rumba" was formed, which could be piloted by users from all over the world.

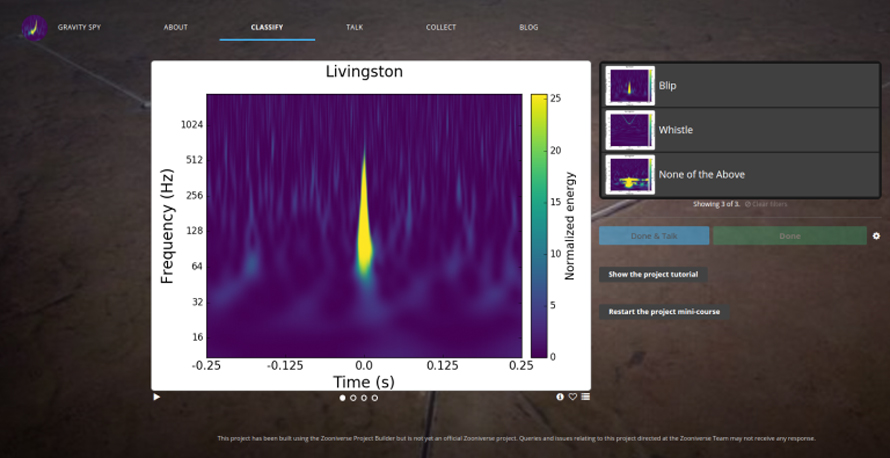

The launch of the first Tashbota is scheduled for the end of this month, and it will work steadily in June. Then you can personally try to fly it. In the meantime, the most impatient users can practice in an online demo in a test pool (or, as it is called here pompously, “underground aqua-laboratory”), filled with plastic ducks, which need to be collected. Each is given five minutes. And this, by the way, is really quite fun.

Even from Russia, the robot responds fairly quickly, it is easy to control, although unassembled ducks were not detected (due to the habraeffect, one may have to wait for their turn to the robot a little longer).

Crowd power

The idea of asking for help from the public to solve big problems is not at all new. In 1715, mathematician and astronomer Edmund Halley (after whom Comet Halley was named) published a map predicting the time and path of future solar eclipses. Since Halley could only be in one physical place during an eclipse, he issued a “request to the curious” and asked them to capture their location and how the sky looked during the eclipse, asking to especially note the “duration of total darkness”. This first crowdsourcing was successful, and, after gathering information from the public, Halley created a second, even more accurate map that helped predict the eclipse in 1724.

Eclipse Map of Halley

Today, technology makes it possible to add real interactivity to Halley’s methods. People can be involved not only in the process of collecting and transmitting information. People can do more interesting and varied work, thus getting something from the process in return. In 1991, almost 300 years after the initiative of Halley, Loren Carpenter, co-founder of Pixar, gave a memorable demo broadcast at a computer graphics conference. He first showed participants the strength of the crowd, and demonstrated that each member of the audience could be used as a separate node to solve the problem.

The “problem” was to force the 5,000 conference participants to play one giant ping-pong game. Everyone present was given a racket, with one green and one red side. In the center of the room was placed a large, as in a cinema, screen, which showed a classic video game, and a computer that scanned the audience, and found out which side of the racket they were holding up – red or green. Each racket held by a member of the audience was counted as one vote (one step up or one step down), and the virtual beating of the ball on the screen proceeded according to the law of such a democracy. An upgraded version of this experiment in 2013 also conducted the BBC. The movement of the ball (or, in this case, the shark) is rather slow, and it is not very interesting to observe, but to be in the audience, and to try to work as a single unit to achieve a common task is quite.