How the myth about visuals, auditory and kinesthetics appeared, and why the model of the dominant learning style is harmful to humans

While educators ring the bell, fearing that ChatGPT will destroy the education system, they themselves are breaking it from the inside with the popular neuro-myth of the dominant learning style.

Questionnaire of the Higher School of Economics showed: 80% of university professors believe that students can be divided into visual, auditory, verbal and kinesthetic. Wider international study speaks: 89.1% of educators believe that people learn better when they receive information in “their learning style.”

What is the problem

Suppose a student has passed a dominant style test and is placed in the auditory category. He may decide that there is no point in studying “visual” or “verbal” subjects such as journalism or theater arts. If such a student does not get the expected grades or enjoyment of learning, he will simply attribute failures to inconsistency with his style.

But it is worth distinguishing between the preferred method of obtaining information and the effective one. Obviously, to learn a foreign language, it is necessary to use more than just the eyes. How, for example, to learn an accent from pictures?

On the other hand, teachers who are forced to adapt their programs to mythical learning styles spend time and money on this when they could be concentrating on other, proven methods.

Schools and universities, as well as teaching aids for educators, recommend taking into account the concept of a dominant learning style, and sometimes this reaches the point of absurdity. For example, in the material of the reference system “Education” in Vorkuta, an educational psychologist advises teachers to monitor their appearance when teaching visuals, and to work with kinesthetics, “gentlely touch, hug and pat the child on the back.”

A neat image, it seems, is a social norm – visuals have nothing to do with it, and the recommendation for teaching kinesthetics is somewhere near the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation.

Where did this come from

There are more than 70 classifications of learning styles, but the most popular of them is VARK. It divides people into visuals (Visual), auditory (Aural), verbal (Read / write) and kinesthetics (Kinesthetic).

The model was invented by the New Zealand school inspector Neil Fleming. In 1995, he published an article titled “I am different; Not Dumb: Ways of Teaching (VARK) in Higher Education”. However, Fleming did not provide hard data that would show how learning outcomes can differ from what subject students are studying.

In addition, Fleming did not create the concept of VARK from scratch. In fact, he came up with one letter – R.

Back in the 60s, a group of American psychologists introduced the VAK model – like VARK, but without verbals. They decided that learning is a complex process that, in addition to cognitive abilities, includes sensory and motor functions. According to the VAK model, the human brain processes information through three main channels: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic.

It turns out that Neil Fleming only supplemented the VAK with the fourth method – “verbal”, that is, the perception of information through reading or writing. And besides, he turned out to be a more talented marketer, since he was able to appropriate the existing concept for himself.

What Science Says

At the heart of the dominant style neuromyth lies the misconception that each brain develops differently and therefore that each person learns differently.

Indeed, out of a hundred billion neurons that the brain has at birth, a unique network of synaptic connections is formed, but this development does not make the brain so individual that a person has a dominant way of receiving information.

On the contrary, the visual, auditory and kinesthetic areas are interconnected: when we hear something, not only the auditory area is activated, but also the visual and kinesthetic areas. For example, sometimes it is enough to engage the verbal area and read that someone has yawned, as the kinesthetic area is immediately activated, and the person yawns in response.

In 2006, American educational consultant Will Thalheimer offered a $1,000 award to those who can prove that dominant style training is effective. Eight years later, he raised the prize pool to $5,000.

The award is still waiting for the winner, but it is unlikely to wait for him: since then, there have been many rebuttals of the concept of VARK and the like.

Indiana University professor Polly Husman and colleagues study, during which 426 students were asked to complete the VARK questionnaire. Next, the students were given tasks to complete, based on their learning style. In reviewing the tests, Husmann found that students did not use the dominant style to get information, and those who tried to adapt learning to fit their style failed the test. The scientist believes that students adhered to certain learning habits that were once formed, and it was too difficult to change them. It seemed like the students were only interested in their dominant learning style, but weren’t really going to adapt to it because it wouldn’t matter.

Other study showed that students who preferred to learn visually thought they would be better at remembering information from photographs, while those who preferred oral material thought they would be better at remembering words. But these preferences had nothing to do with how students actually remembered words or pictures.

“There is evidence that people do try to relate to tasks according to what they consider to be their learning style, but this does not help them.,

— Daniel Willingham, psychologist, professor of psychology at the University of Virginia.

IN article Journal of Educational Psychology it is said that no relationship was found between the preferences of learning subjects (visual or auditory) and their performance in reading or listening tests. Instead, visuals performed better on all kinds of tests. “Educators may actually be doing a disservice to auditory learners by constantly adjusting to their auditory learning style,” the researchers said, “instead of focusing on strengthening other skills.”

Passing the VARK test

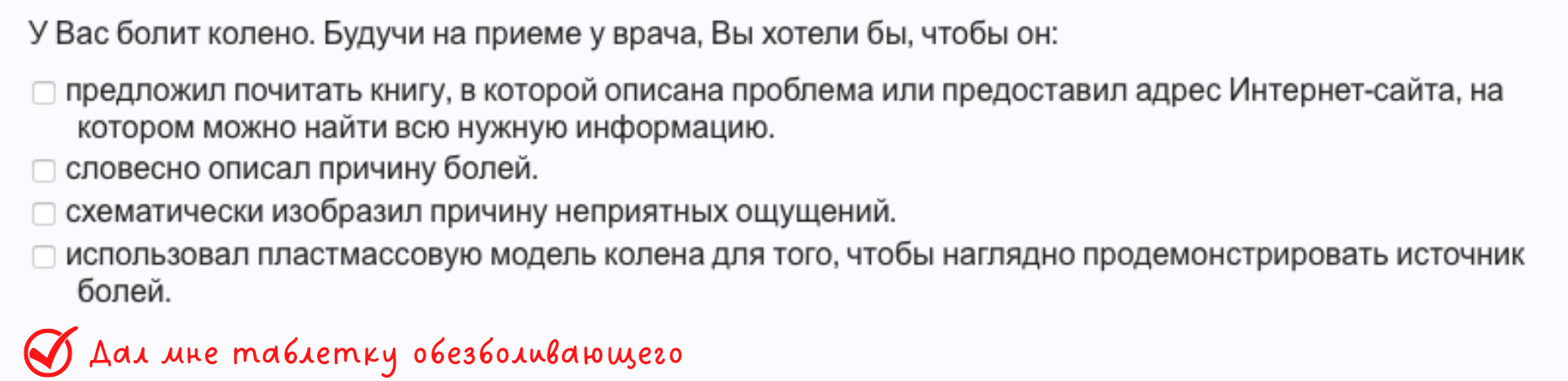

IN questionnaire VARK, which has been translated into many languages, including Russian, has 16 questions in total. Many of them ask strange situations or outdated ways of solving a particular problem. For example, the question about cooking includes two items with a cookbook, although now you can google the recipe or ask ChatGPT.

And in this situation, I would even prefer the fifth option.

The VARK questionnaire, in some way, refutes its own idea. He put me in the category of “multimodal” people, that is, those who use different styles when teaching. According to them, the majority of such people on the planet. And this is natural, because in different situations and objects, different ways of obtaining information are needed.

Are there proven and effective ways to learn?

Before limiting yourself to one style of learning, it is important to understand the actual and effective methods that have been helping to improve the absorption of information over the years. Remarkably, most often these methods are easier and easier to implement into training than to adapt to your style on the VARK test.

Cognitive psychologists determined six key strategies for flexible and effective learning. But even in these theories, scientists emphasize that there is no one priority way of learning that will work always and for everyone. Teachers and students should use different methods and mechanics, and in some cases a combination of them.

Interval. An effective approach to learning is a strict understanding of how much you do and at what time you do it. Any information is absorbed better if you give it an hour a day. Conversely, the material will not take root if the student spends 7 hours on it in a row, without a break for any other business or sleep. Short lessons of 20-30 minutes or repetition of the material every day will provide better memorization.

Alternating ideas. When studying the material, do not focus on one topic, but try to look for related ideas where you can apply the knowledge you have gained. For example, when learning a foreign language, it is not necessary to do many tasks of the same type with a rule you have just learned, it is better to find a text where the same topic is introduced with the rules that you already know. The rotation strategy may seem difficult and lead to many mistakes at first, but in the long run it helps to better assimilate the material and fix it in long-term memory.

The practice of searching or retrieving. Using this strategy, students test their knowledge without referring to notes. With self-study, you can write out all the knowledge on the subject that you have in your head. In the classroom, this strategy is reflected in quests and quizzes. After such entries, it is very important to return to your notes and check what has escaped your attention. This approach ensures frequent retrieval of information, which contributes to the active work of the brain.

Study. Students need to ask themselves “how?” questions more often. and “why?” in order to better work out the details of any topic being studied. Attempts to describe and explain your understanding of the material will help you understand where there are gaps and inconsistencies, as well as look at learning from the other side, tie all the information together. Questions must be answered without a summary.

Double coding. Dual coding goes against VARK, as this method combines two different types of information: verbal and visual. Any complex text is assimilated better, as it is supported by visual images – diagrams, diagrams, pictures. That is, each student must learn both the verbal part and the visual part. In the description of the strategy saidthat this approach allows students to encode information in the brain at different levels.

Specific examples. Concrete information contributes to long-term memorization because it is based on real examples. An abstract explanation, especially for beginners, can be vague and difficult to understand. Students create their own relevant examples based on the knowledge they have, so this strategy works well.

Why the VARK myth is popular

VARK made people special: you don’t have to delve into the details of the material and agree that it’s difficult for you – just say that you are different: visual or kinesthetic. Even the title of an article by Neil Fleming emphasizes this idea:I am different; not dumb: Methods of Teaching (VARK) in higher education”.

However, limiting ourselves to only one “individual” type, we forget that a person quickly gets used to information and stops assimilating it. Strategies that seem easy will not help learning in the long run, they will only help you become “special” and escape from real, complex, but working methods.

Learning requires a lot of attention, it must be consistent, and the knowledge gained must be consolidated by practice and repetition of the material. It is impossible to learn a subject using life hacks from TikTok, and for high-quality learning, you need to use all ways of perceiving information.

Surprisingly, the alleged individualization of learning with VARK makes learning non-individual. It is easier for teachers to agree that there are four categories of people than to understand that each person is really individual and many factors influence learning.