A brief history of the verb to be in English

“To be, or not to be, that is the question” – “To be or not to be, that is the question.”

This phrase of Hamlet is considered one of the most recognizable in world literature. And it directly touches the topic that we want to talk about today. Let’s talk about the history of the verb to be.

The origin of to be and its forms is a true linguistic detective story in which even linguists do not know the answers to all questions. Let’s try to figure it out.

To be: what is this fish in modern English

According to statistics Word frequency data, the verb to be and its forms take the second place in terms of frequency of use among all the lexemes in the English language. And among the verbs, this is actually # 1, which is more than three times ahead of its closest opponent – have.

Students who study English as a foreign language become familiar with it already in the first lesson. This is the very first verb they learn, because the vast majority of starting lessons begin with the phrase “My name is”.

However, the presence of as many as eight forms of the verb to be continues to amaze students even at high levels of language proficiency. After all, they are very different from each other. Let’s go over all.

Be – infinitive, subjunctive and imperative.

It’s good to be here. – It’s good to be here.

He needs to be here at 6 o’clock. – He needs to be here at 6 o’clock.

Be here at 6 o’clock. – Be here at 6 o’clock.

Am – present, first person singular

I am here now. – I am here now.

Are – present, plural first and third person, and singular and plural second person.

We are here now. – We’re here now.

They are here now. – They are here now.

You are here now. – You’re here now.

You are here now. – You are here now.

Is – present, third person singular

He is here now. – He’s here now.

She is here now. – She’s here now.

Was – past tense, first and third person singular

I was here. – I was here.

He was here. – He was here.

It was here. – It was here.

Were – Past tense, first and third person plural, second person singular and plural, and subjunctive.

We were here. – We were here.

You were here. – You were / You were here.

If I were you, I would be here at 6 o’clock. – If I were you, I would be here at 6 o’clock.

Being – present participle, gerund

I like being here. – I like being here.

Been – perfect participle (third form of the verb)

I have been here. – I was here.

The reason for this variety of forms and their dissimilarity is hidden in the Old English language and even a little further in history.

The main secret of the verb to be

And it consists in the fact that in the Old English analogue verbs to be there were actually … two. And each of them changed in shape depending on time, person and number.

Meet bēon and wesan. Both verbs are translated as “to be”. They complemented each other and in some cases were interchangeable. But there were still nuances of use.

For example, wesan was used in most situations, and bēon was mainly used to form future tense and general statements. But all the same, everything was rather complicated and confusing.

In Old English, these verbs were also irregular or anomalous verbs. Their declensions did not follow the generally accepted rules.

And since there is a lot of tension with examples of Old English texts, let’s take the classics – Beowulf.

Original in Old English

Habbað we to þæm mæran micel ærende,

Deniga frean, ne sceal þær dyrne sum

wesan, þæs ic wene.Translation into modern English

Have we a glorious embassy to proclaim unto earl-moot,

To the King of the Danes, nor shall I keep secrets from thee,

To this I will agree.Russian adaptation:

And we won’t hide

from our noble thoughts,

about which you will soon find out.

The words bēon and wesan, or, more precisely, their ancestors from the Proto-Indo-European language, strongly influenced the creation of the verbs “to be” in the entire Germanic group of languages. This is especially noticeable in German.

We will not focus too much on it, but even a non-linguist will notice that the modern forms of the verb “to be” in German are related to their counterparts from Old English.

It is also interesting that a single grammatical norm in the Old English language simply did not exist. And with the arrival of the Normans in Britain in the X-XI centuries, a global change in English began.

We will not dwell on this now. If you want more details about this, read the material “The history of the English language is literally on the fingers“.

To be in Middle English, or Great Confusion

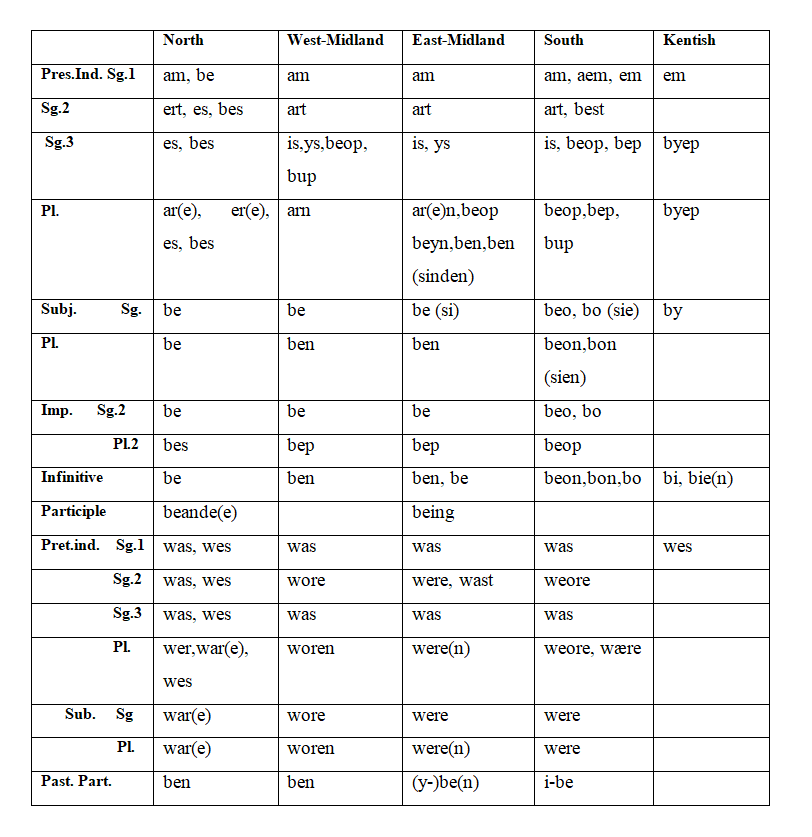

Essentially Old English and Middle English are two completely different languages. Complicating the situation was the fact that each region had its own characteristics that influenced the pronunciation and spelling of words.

Yes, the original verbs bēon and wesan were still used as a basis. But depending on the region and the strength of the influence of the Norman language, everything is quite confused. Some forms replaced others, spelling and pronunciation changed.

This is how the forms of the verb to be looked in the XII century in different parts of Britain.

English dialects were another problem for communication. Sometimes it got to the point that a Briton from the northern part of the country could not understand a southerner.

The sound of the verb to be was also strongly influenced by the Great Vowel Shift. Es has become is in many variations. Bes to bis and so on. Because of this, a jumble of options has formed, in which even linguists are confused.

English developed in close contact with French and German, so their influence can be traced. Andrea Moro wrote a whole monograph about this called “A Brief History of the Verb To Be”… Our article title is a reference to this particular book. It will be interesting even for people who are far from linguistics. The only negative is expensive.

To be in Early Modern English: Typography and Shakespeare

An end to the variety of options was put by William Caxton, who was the first in Britain to create a printing press in the 1470s. It was he who established the “only correct” spelling of the verb to be and its forms. With minimal changes, they have survived to this day.

We talked more about Caxton’s personality and his role in the formation of the English language in the article “When you learned the pronunciation of English words, you swore to William Caxton, even if you didn’t know who he was.“

The printed word has almost completely squeezed out regional variants in a hundred years. And when in the second half of the 16th century the linguistics of the English language began to emerge as a science, in all books it was the printed forms of the verb to be indicated as correct.

Regional peculiarities still remained, especially in the hinterland among the illiterate strata of the population, but among the educated English, the differences in the grammar of the language became less and less noticeable.

And when, at the end of the 16th century, William Shakespeare began writing his plays, the grammar of the English language – in particular, the form of the verb to be – was more or less settled.

Let’s give as an example a few quotes from his works:

The most famous monologue from Hamlet:

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them.Per. B Pasternak

To be or not to be, that is the question. Is it worthy

Resign ourselves to the blows of fate

Or it is necessary to resist

And in mortal combat with a whole sea of troubles

End them?

At the time of Shakespeare, the pronoun of the second person singular thou and the corresponding form of the verb to be – art were still actively used. Today it is dusty archaism.

Already in the Middle Ages, thou was considered an appeal of the higher to the lower. It was considered indecent to use it among equals, so it gradually fell out of use, and with it the verb art.

To illustrate, here’s the first scene from Romeo and Juliet:

SAMPSON

Me they shall feel while I am able to stand: and

’tis known I am a pretty piece of flesh.GREGORY

‘Tis well thou art not fish; if thou hadst, thou

hadst been poor John. Draw thy tool! here comes

two of the house of the Montagues.Per. T. Shchepkina-Kupernik

Samson.

They will feel me as long as I can hold on.

And I’m, you know, not a bad piece of meat!Gregory.

It’s good that you are not a fish, otherwise it would be you

dried cod. Draw out your sword: here they come

two from the Montague house!

And let’s take another excerpt from the play “King Lear”:

I pray you, father, being weak, seem so.

If, till the expiration of your month,

You will return and sojourn with my sister,

Dismissing half your train, come then to me:

I am now from home, and out of that provision

Which shall be needful for your entertainment.Per M. Kuzmina

Take your weakness into consideration.

Until the end of the month

Return to your sister and live there,

Dissolving half of the suite, then to me.

Now I’m not at home, and there are no supplies,

With which I could support you.

But at the same time, Shakespeare actively uses the forms of the verb, which became obsolete already in the 17th century – wast and wert.

Here, for example, is sonnet # 82. Let’s give it in full:

I grant thou wert not married to my muse,

And therefore mayst without attaint o’erlook

The dedicated words which writers use

Of their fair subject, blessing every book.

Thou art as fair in knowledge as in hue,

Finding thy worth a limit past my praise,

And art enforced to seek anew,

Some fresher stamp of the time-bettering days.

And do so love, yet when they have devised,

What strained touches rhetoric can lend,

Thou truly fair, wert truly sympathized,

In true plain words, by thy true-telling friend.

And their gross painting might be better used,

Where cheeks need blood, in thee it is abused.Per. S. Marshak

You are not betrothed to my muse,

And your judgment is often lenient,

When the poets of our days

Eloquently devote work.

Your mind is as graceful as your features

Much subtler than all my praises.

And inevitably you are looking for lines

Newer than those that I wrote to you.

I’m ready to give in to my rivals.

But after rhetorical attempts

The truth of these words will become clearer,

What is just a talking friend writing.

Bloodless people need bright paint

Your blood is already red.

So it turns out that already in the 16th century the verb to be acquired almost the same forms as in modern English. Except for a few.

Medieval linguists who study the theory of language, and in fact create it from scratch, picked up the rules for using the verb, and wrote textbooks that taught children to read and write.

Surprisingly, over the past 500 years, the use of the forms of the to be verb has changed little. The thing is that with the invention of typography, the language settled down and subsequently changed slowly. Actually, this is one of the reasons why Shakespeare’s works are understandable to us almost without problems, and Chaucer, who worked two centuries earlier, is already difficult to read.

The history of changes to the verb to be is similar to an action-packed blockbuster. First, from two different verbs, one emerged, but with different forms. Then, over the course of several centuries, variations multiplied, until a single standard was approved by the book printer Caxton and medieval poets along with linguists. And if you know all this, then it no longer seems strange why the forms of the verb to be look so different.

Want even more interesting stories from which you can and should learn English? Sign up for a free trial lesson with a teacher and enjoy improving your language.

Online school EnglishDom.com – we inspire to learn English through technology and human care

For Habr readers only first lesson with a tutor in an interactive digital textbook for free! And when you buy classes, you will receive up to 3 lessons as a gift!

Get a whole month of premium subscription to the ED Words app as a gift… Enter promo code june_2021 on this page or straight in the ED Words app… The promo code is valid until 08/01/2021.

Our products:

Strengthen your speaking skills and find friends in conversation clubs

Watch a video of life hacks about English on the EnglishDom YouTube channel